FAqs

- How does school funding work in Vermont now?

- What is income sensitivity and how does it work?

- How is per-pupil spending calculated?

- How is it different from the foundation system we had before?

- What’s unfair about who pays now?

- What are these tax cliffs everyone’s talking about?

- Why should we move to income-based taxes for schools?

- Why did my education tax bill go up so much more last year?

- Does Vermont spend a lot more than most other states on public education?

- Is education spending out of control?

- Is local control driving education spending higher?

- Will a foundation system make education funding in Vermont more equitable?

- Is it better to have the state or communities decide on how much to spend on schools?

- Would a foundation system like the governor’s plan mean we spend more or less on schools?

- How would moving to fewer districts affect Vermonters’ ability to have a say in their local schools?

- Would the governor’s plan increase the use of vouchers/school choice?

- How will we vote on school budgets under the governor’s plan?

- Does school consolidation save money?

- How is the House plan similar to the governor’s?

- How is the House plan different from the governor’s?

- Do the same concerns about a foundation system apply to the House plan?

- How would the homestead exemption work and what happens to income sensitivity?

- What happens now?

- If it’s such a good idea, why haven’t we done it already?

- Is income more volatile than property value?

- Will rich people leave the state if taxes are more progressive?

- As more Vermonters age into retirement, will the income tax base shrink and the state get less revenue?

- Can rich Vermonters hide their income to avoid school taxes?

Education Funding 101: how the system works now

How does school funding work in Vermont now?

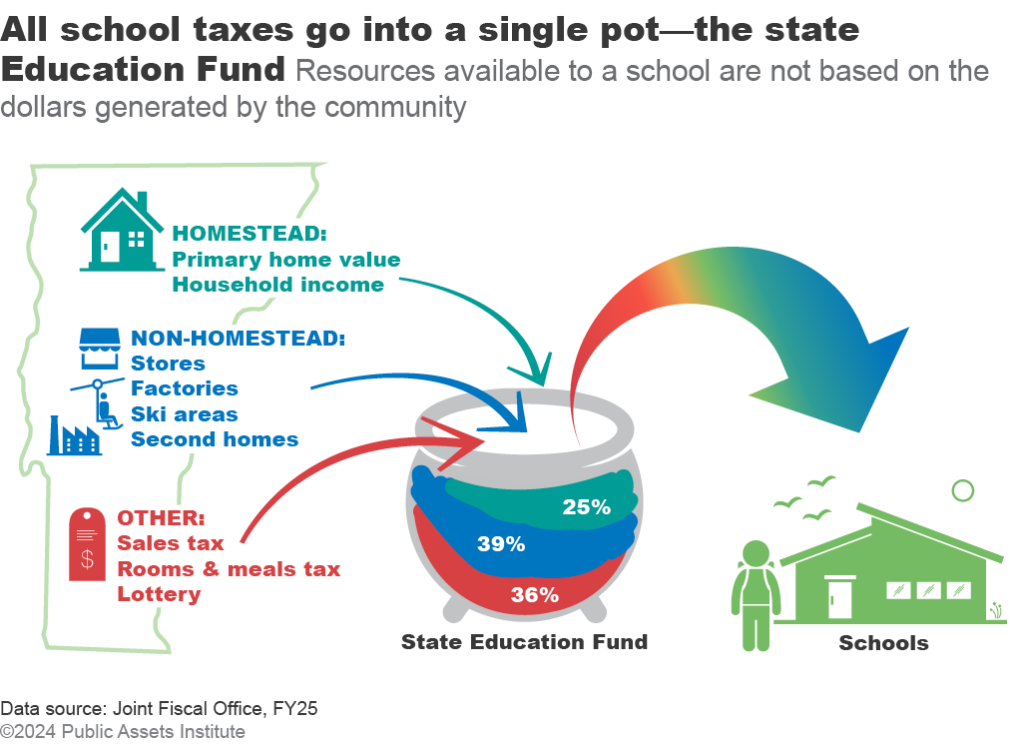

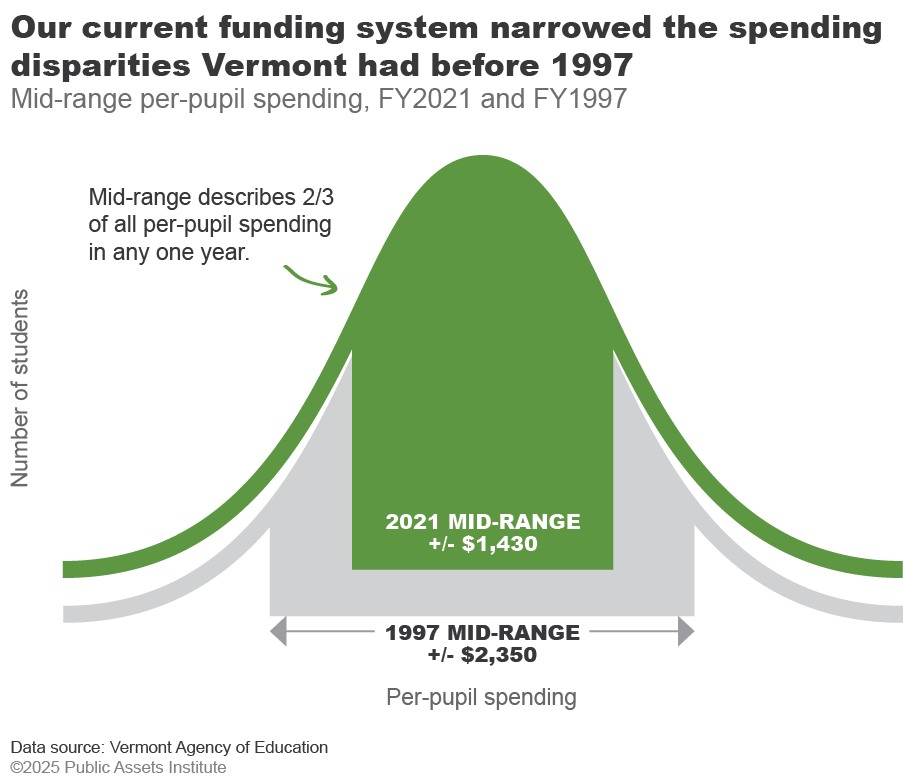

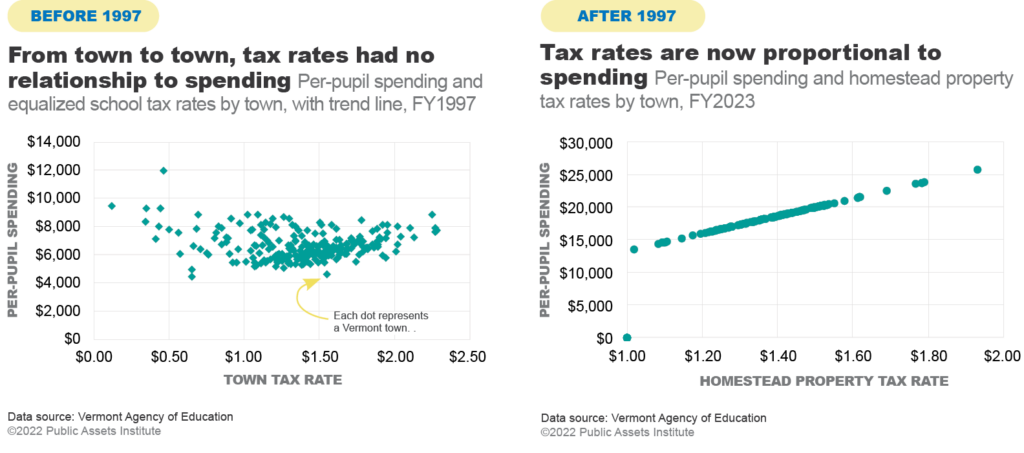

In Vermont, unlike most states, school funding is not dependent on the wealth of the town. Instead, Vermont has one shared statewide pot that all districts draw on to fund their schools. This is important for two reasons: first, it means that we’ve been able to narrow the disparities in education spending across communities. Second, it means that your tax rate is determined by your per-pupil spending, not your town’s property wealth. Finally, for many Vermont homeowners, school taxes are based on income, which better reflects their ability to pay and continues a policy that Vermont adopted more than 50 years ago. (more on that below). PAI 101 resources

What is income sensitivity and how does it work?

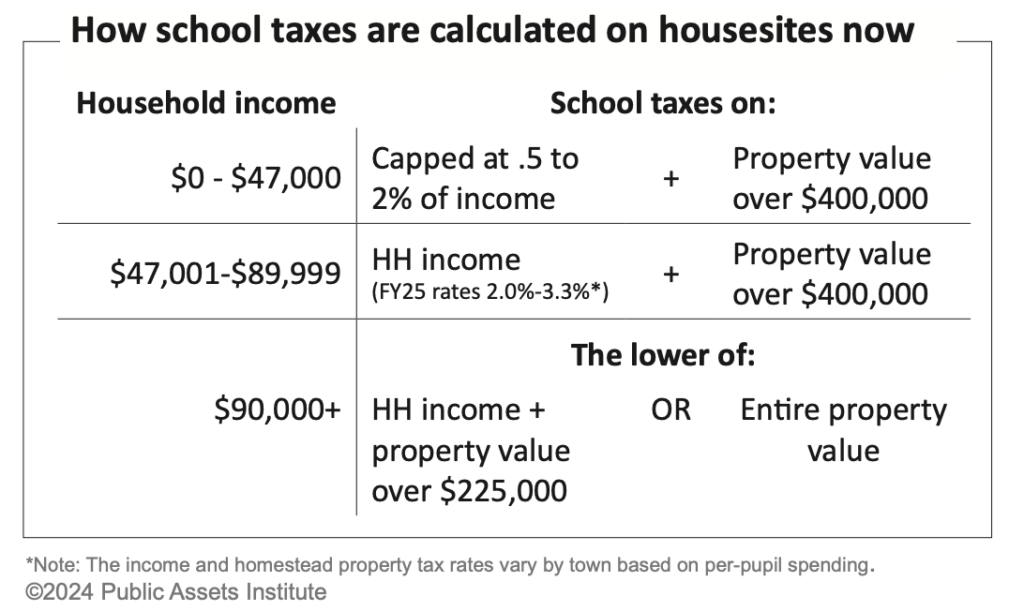

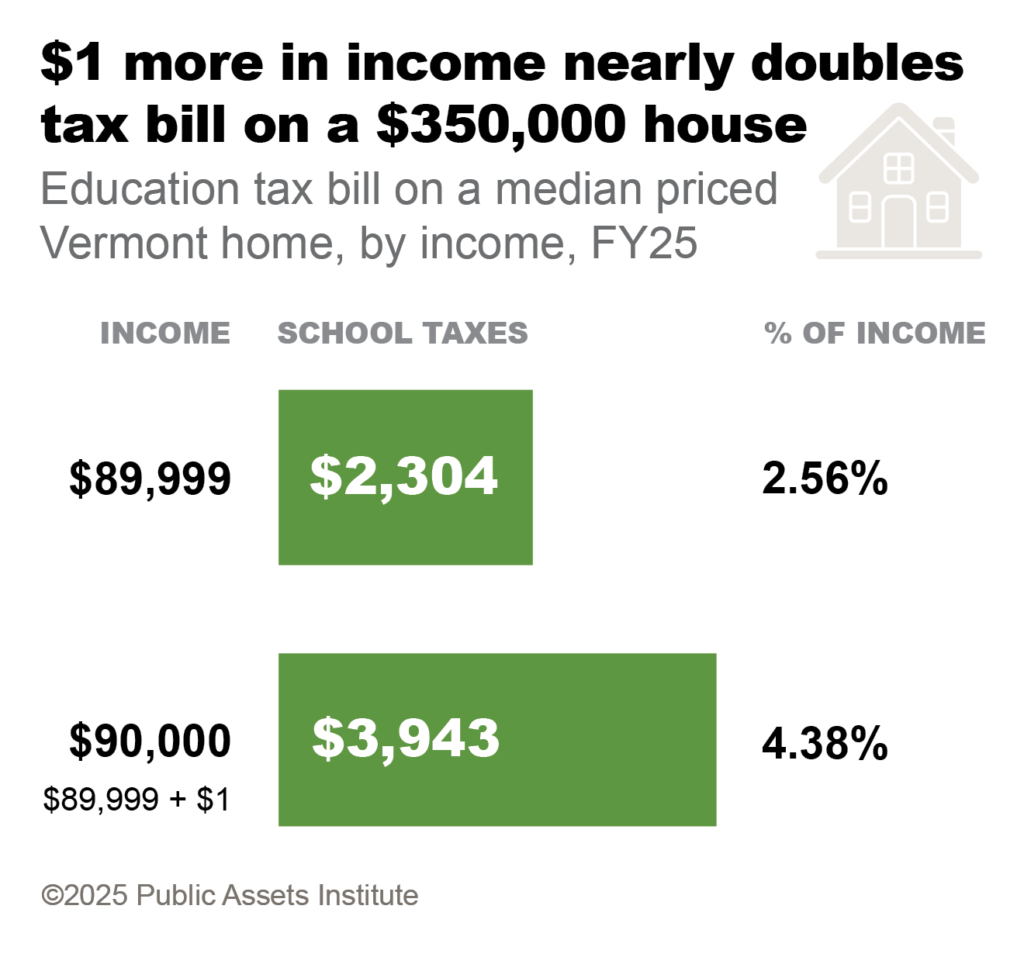

While it’s calculated as a property tax credit, income sensitivity essentially allows low- and middle-income Vermonters to pay their school taxes based on income, which is a better measure of their ability to pay. Up to $47,000 in household income, school taxes are capped at 2% of income. Between $47,000 and $90,000, homeowners pay a local income rate, which is based on their town’s spending per pupil. But at $90,000 or above, taxpayers must also pay a property tax on any portion of their home value above $225,000. The problem is that none of these thresholds have been raised in decades (that $47,000 hasn’t changed in at least 40 years), meaning that fewer Vermonters qualify and those that do get

less help

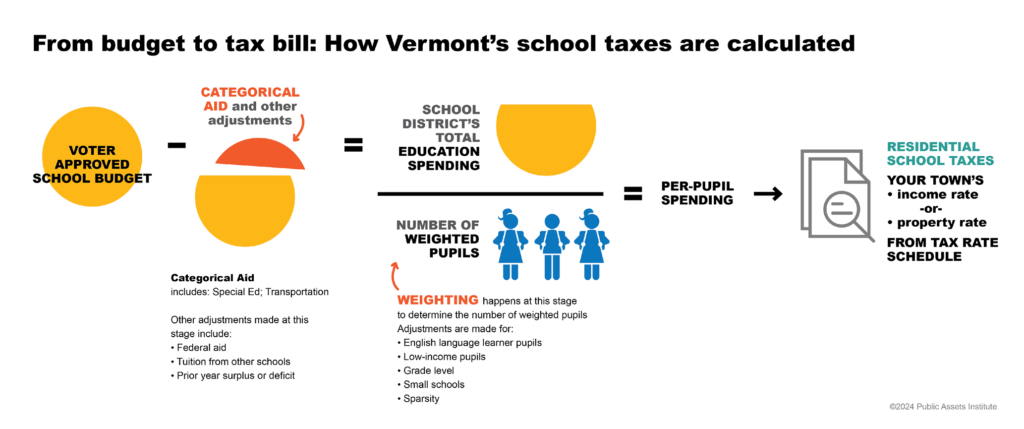

How is per-pupil spending calculated?

How is it different from the foundation system we had before?

Before the Brigham case declared the state’s

foundation system unconstitutional, there were stark disparities between rich and poor towns because rich towns could raise and spend as much as they wanted above the foundation amount. The foundation amount essentially acted as a ceiling for poor towns and a floor for rich towns. In fact, the system we have now succeeded in narrowing the disparity among towns, and making things fairer for taxpayers by ensuring they get the same per-pupil spending for the same tax rate.

How to fix the unfairness in who pays school taxes now

What’s unfair about who pays now?

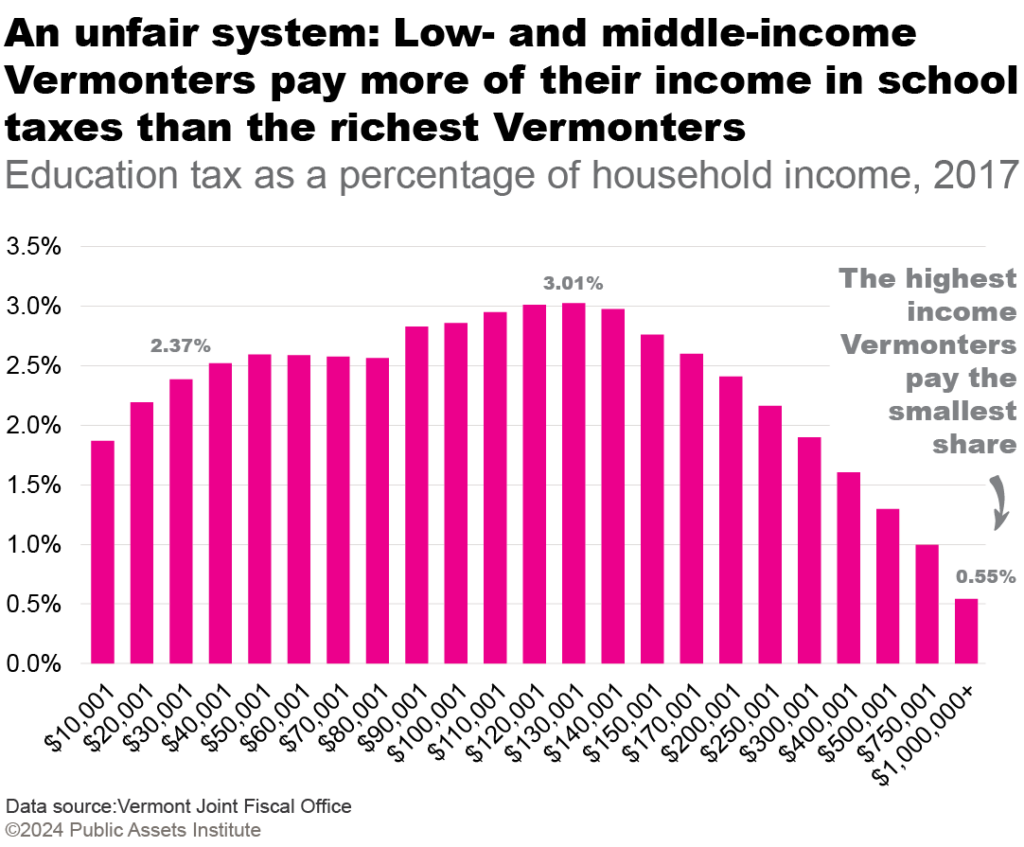

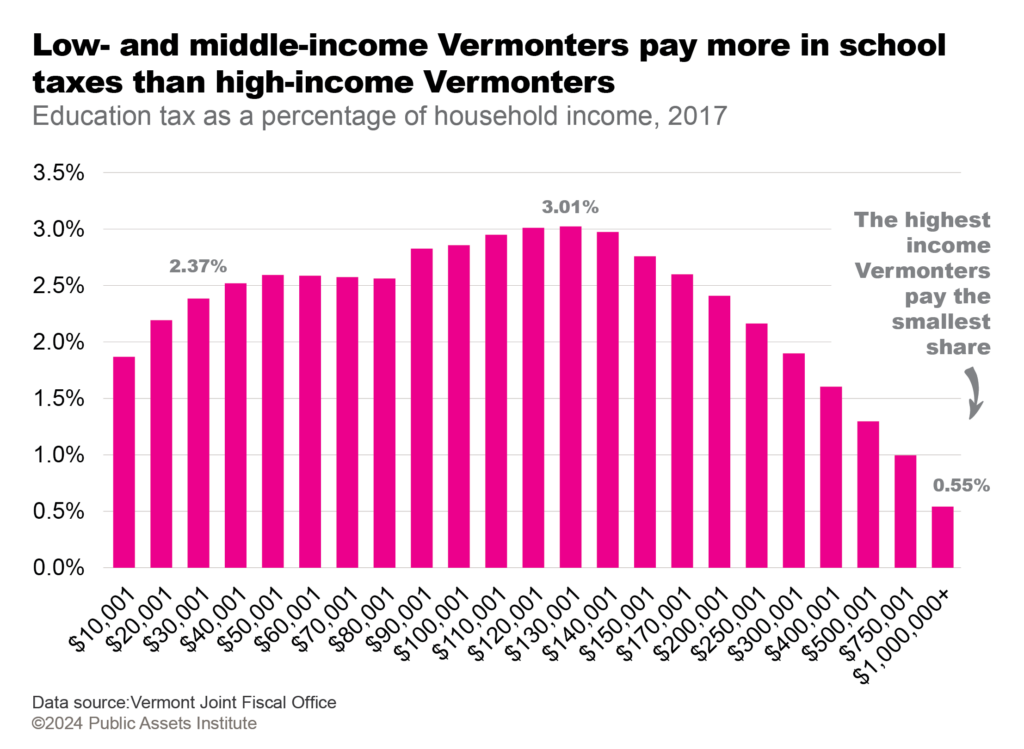

Two things: low- and middle-income Vermonters pay a bigger share of their income in school taxes than higher-income Vermonters and they face tax cliffs that can cause big jumps in their bills even if their district’s spending hasn’t changed.

What are these tax cliffs everyone’s talking about?

Many Vermonters—and the share is growing—pay a combination of income and property taxes. When homeowners’ incomes or house values pass certain thresholds they have to pay both, creating sudden jumps in taxes even when school spending doesn’t change. Property values have been going up in many parts of the state, but these thresholds have not been changed for decades. Updating them for inflation and changes in property values would ensure low- and middle-income Vermonters benefit from income sensitivity

Why should we move to income-based taxes for schools?

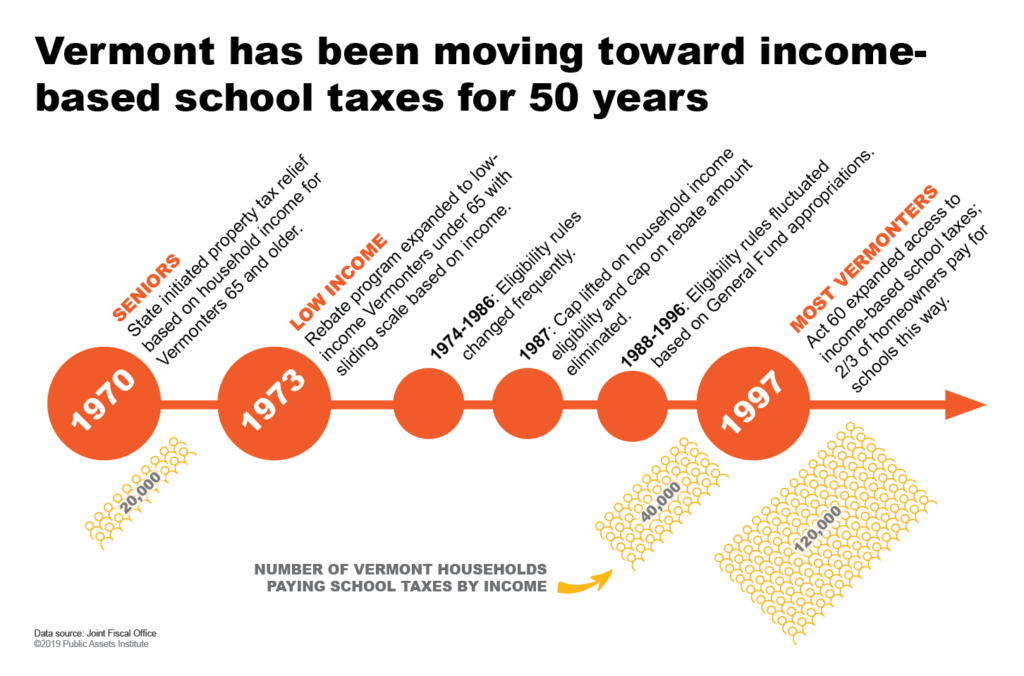

When we first started our public education system, property was the best measure of Vermonters’ ability to pay. Land, cows, sheep— these were indicators of wealth. But that’s changed now. Most Vermonters have income from jobs, and they don’t sell a cow or part of their house to pay their school taxes—they pay taxes out of their income. Income is now a much better measure of ability to pay. But don’t take our word for it—the Tax Structure Commission wrote the book (actually a long report) about it. And income-based taxes aren’t a new idea—we’ve been doing it for 50 years.

What happened in FY25

Why did my education tax bill go up so much more last year?

The primary cost drivers in recent years would have hit no matter how many districts we have or who decides how much to spend. The Agency of Education identified the main reasons for the FY25 spending increase: inflation; health insurance; the growing need for mental health services for students; and the loss of Covid-era federal funds. All of these pressures were unavoidable and affected other states as well. So most of the tax increase was driven by cost increases, not the funding system. And if you lived in a town where property values increased more than average, that could push taxes up even further. Another significant change was in how the state calculates per-pupil spending: New pupil weights also took effect in FY25, so towns with more kids in weighted categories could spend more without as big an increase in taxes, while towns with fewer weighted kids saw higher rates than they would have before the changes.

Does Vermont spend a lot more than most other states on public education?

A better question to get at whether we’re spending the right amount is to ask if Vermont is meeting the needs of all kids with the resources it provides. Most educators and parents would say schools need more resources, not fewer. But to answer the question directly:

- Vermont has been one of the higher spenders by these comparisons for decades as have the other Northeast states. Vermont has been consistent in the share of state resources dedicated to public education.

- Many states that spend less on education than Vermont often do so because they underfund poor districts and underpay teachers while allowing wealthy communities to concentrate resources in their local schools; they have lower statewide spending per pupil because they operate a less equitable system.

- In recent years, Vermont has in fact had slower growth than many states—we’re right in the middle. That’s because the cost drivers that hit Vermont so hard in FY25—mental healthcare costs for kids, increasing healthcare costs for staff, inflation and the loss of Covid funds—all hit other states too.

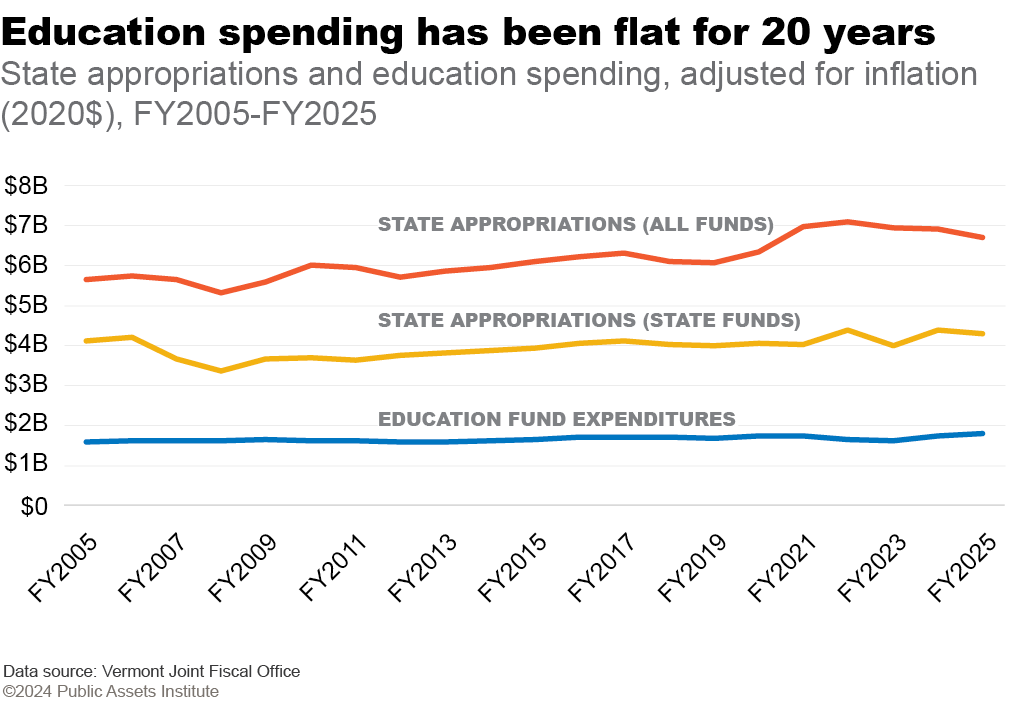

- Total education spending has been flat for 20 years after adjusting for inflation, just like the rest of the state budget. And per-pupil spending has grown about 1% a year after adjusting for inflation. And that’s taking into account increased costs for mental healthcare, information technology, and school security.

Is education spending out of control?

Education spending has been flat for 20 years after adjusting for inflation, just like the rest of the state budget. And that’s taking into account increased costs for mental healthcare, information technology, and school security.

Is local control driving education spending higher?

The system was designed to give local voters the authority to decide how much to spend on schools and therefore how much to tax themselves. Generally, other districts’ choices have only very modest impacts on another town’s tax rate. But when there are significant cost pressures across the whole system, like in FY25 when virtually all districts faced increases outside their control, tax bills go up for everyone. The Agency of Education identified the main reasons for the FY25 spending increase: inflation; health insurance; the growing need for mental health services for students; and the loss of Covid-era federal funds. All of these were unavoidable and affected other states. In spite of these pressures, FY25 showed that local control does restrain spending: ⅓ of districts sent their school boards back to the drawing board until they came back with lower budgets.

Questions about the governor’s Education Transformation Proposal

Will a foundation system make education funding in Vermont more equitable?

A foundation funding system sets a fixed base amount of spending for all districts—a one size fits all approach. But the problem that Vermont had with its foundation system before 1997—and most other states still have—is that richer towns could raise more money if they wanted. That resulted in stark disparities in funding. The foundation amount essentially acted as a ceiling for poor towns and a floor for rich towns. Then the Brigham family sued the state over those disparities and the State Supreme Court agreed the foundation system was unconstitutional because kids didn’t have equal access to educational resources. Money in the statewide Education Fund is now available to benefit all schoolchildren in the state. And another challenge with a fixed amount approach is that schools aren’t starting from the same place: some schools have older HVAC systems and higher heating costs; other schools have already made drastic cuts to allied arts.

Is it better to have the state or communities decide on how much to spend on schools?

Local voters are only responsible for school budgets and they know what’s going on for kids in their communities, so are more focused on what their local kids and local schools need. Lawmakers in Montpelier are responsible for the entire state budget, which is complex and many steps removed from the needs of individual kids and schools. And because pre-K-12 education is the biggest thing the state does, even small tweaks to the foundation amount multiplied by 80,000 kids add up to big cost savings—or big cost increases. There would be constant pressure to underfund inflationary increases or lower the foundation amount to balance the budget. And in fact, that did happen in the past in Vermont: When a portion of education funding had to be appropriated from the General Fund, lawmakers waited until the rest of the state budget was funded before deciding what to transfer for education.

Would a foundation system like the governor’s plan mean we spend more or less on schools?

While not all the details are available yet, the foundation amount the governor is suggesting is pretty close to the state average spending per pupil. That means for some districts it will be more than they spend now, while higher-spending districts would likely face cuts. Different schools have different needs. If the concern is getting lower-spending districts additional funds, we can do that without forcing others to make big cuts. A foundation plan would either force higher-spending districts lower, or increase disparities by allowing them to spend above the foundation amount.

How would moving to fewer districts affect Vermonters’ ability to have a say in their local schools?

Vermonters have a long tradition of participating in decision-making about their schools. Moving to fewer districts would make it harder for local communities to have a say in their school budgets and priorities. School boards are a great way for community members to get engaged in schools and public policy. Many state and community leaders get their start serving on school boards. There’s not necessarily a right answer about how many boards we should have, but Vermonters should have a say in that decision.

Would the governor’s plan increase the use of vouchers/school choice?

While the details of the governor’s plan for a choice lottery for all kids are still emerging, this administration has consistently supported school choice. Vermont has a long history of tuitioning kids to go to schools outside their districts. But there are a lot of concerns about increasing school choice because private schools are not subject to the same requirements as public schools and the funding often goes to well-off families that can afford to send their kids to private schools and would whether they received public money or not. And since the ruling in Carson v. Makin that declared religious schools could not be excluded from choice systems, we’re seeing more public money go to private schools that aren’t subject to the same rules as public schools, including religious schools and schools out of state.

How will we vote on school budgets under the governor’s plan?

It’s not yet clear how large consolidated districts would work. The governor is proposing moving from 119 school districts to 5, with just 5 school boards responsible for much larger districts. There are still a lot of questions about how school budgets will be determined, how the funds will be distributed among schools within districts, and who would make these decisions. But the concern is that the administration’s plan would erode public involvement in two significant ways: take away choice on Town Meeting Day about how much to spend on our local schools; and increase the use of vouchers through school choice, which diverts public money to private schools and out of state.

Does school consolidation save money?

Act 46 of 2015 resulted in a number of mergers across the state. Although the Agency of Education has not done a comprehensive evaluation of the effort, other research has found little in the way of cost savings or improvement in outcomes.

Questions about the House’s Education proposal, H. 454

For the bill summary and fiscal note, click here.

How is the House plan similar to the governor’s?

The governor and the House are aligned on the big structural changes:

- Both are proposing moving to a foundation system, where the state sets a fixed spending amount for everyone, with pupil weights, adjusted for inflation and paid for with a statewide property tax

- Both include state-imposed consolidation to fewer districts, reducing or eliminating the role of local school boards

- Both are leaning into property taxes with a homestead exemption approach where some portion of the home value is exempt from taxes

How is the House plan different from the governor’s?

- The House has a longer timeline for implementation

- The House has a higher foundation starting amount than the governor: $15,500 compared to

$13,200 - The governor is proposing expanding vouchers, the House would limit them

- The governor’s homestead exemption proposal is a dollar amount, the House a graduated percentage of value

- The governor would consolidate to 5 districts; the House is asking a Commission subcommittee to offer three possible plans aimed at districts with ~4000 kids (20-21 districts)

- The governor is explicit in the goal of reducing spending on public education and his foundation amount would cut $184 million from public schools; the House is not explicit about funding cuts

Do the same concerns about a foundation system apply to the House plan?

While the House starts from a higher foundation amount and may not have immediate cuts, the same concerns apply:

- The foundation amount would face downward pressure at the state level. It gets tied up in other state budget balancing because it’s such a big part of state spending; before 2018 the GF transfer to the Ed Fund was regularly held up until the budget was resolved, which is why the state eliminated it and in the old foundation system before 1997, it was regularly underfunded to balance the state budget.

- One-size-fits-all approach does not address the biggest cost drivers like teacher healthcare and inflation, or those that hit some districts harder than other such as the cost of mental healthcare for kids.

- It’s difficult to get from where we are now with schools starting from such different places to a more standardized system – some districts have already made cuts, some are building new schools.

- A foundation system reduces community engagement with their schools by eliminating voters’ say in the school budgets and control over how much to spend.

- Vermont’s old foundation system and foundation systems in other states resulted in stark disparities between rich and poor towns; the House plan attempts to mitigate that with limits on spending above the foundation amount and tying spending to what poorer districts can raise.

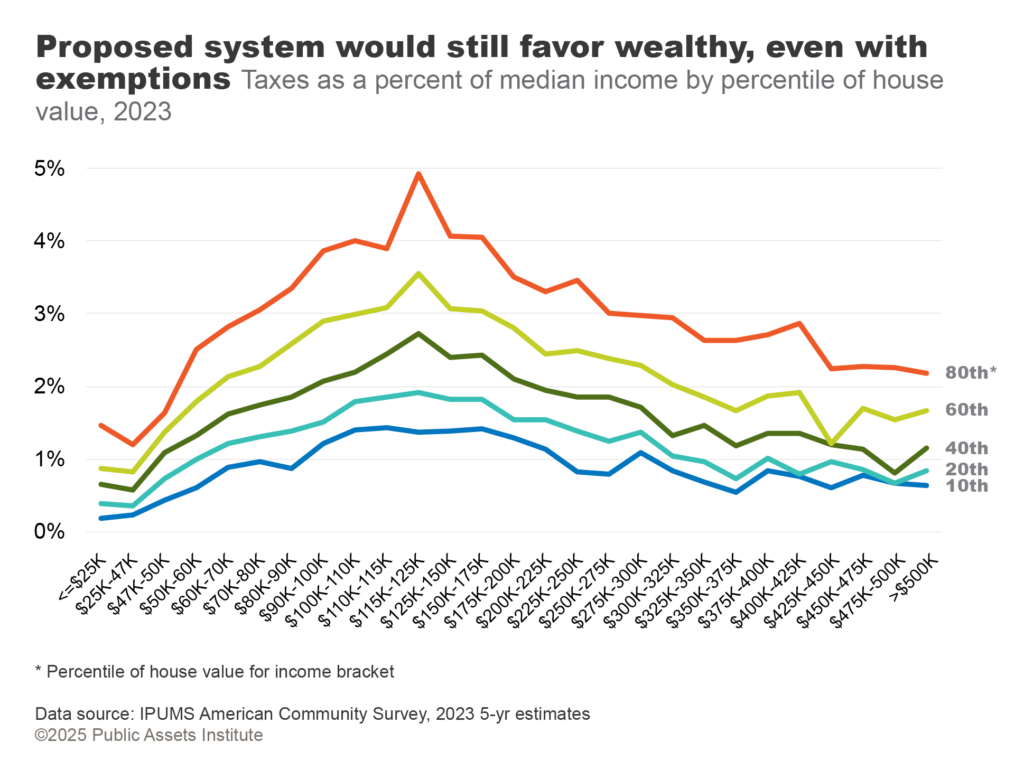

How would the homestead exemption work and what happens to income sensitivity?

Under both the governor and the House’s plans, homestead exemptions would replace income sensitivity. Instead of basing school taxes on income for most Vermonters as happens now, the homestead exemption would return to a system of school taxes driven primarily by the value of the primary home, with some portion of the home value exempt from school taxes for Vermonters with income under $115,000 in the House plan and under $125,000 in the governor’s plan. After 50 years of basing school taxes on income and protecting low- and middle-income Vermonters from losing their homes because of high property taxes, the state would return to a system where the value of the primary home determines your school tax bill. Any plan based on the value of primary homes perpetuates the regressivity of the current system, meaning that the highest income taxpayers would continue to pay a smaller share of their income in school taxes than the low- and middle-income Vermonters.

- Neither plan asks higher-income taxpayers to pay more but

leaves low-& middle-income subsidizing them - Neither plan asks higher-income taxpayers to pay more but

leaves low-& middle-income subsidizing them - Both plans just redistribute the same share of taxes around

households under $115K (or $125K in gov plan) while holding

the highest-income taxpayers harmless - Taxpayers with the same income will face very different bills

- Could result in property tax bills forcing people out of their

homes - Most people have mortgages, so the value of their home

does not wholly belong to them and is not a good measure

of ability to pay

What happens now?

The Senate is working on their version of a plan, then the House and Senate will work to agree on a plan to send to the governor before session ends in May or June. None of the current proposals would go into effect in FY26, which begins July 1. The governor has proposed a one-time $77 million buydown of the tax rates for FY26, which the House concurred with and included in the yield bill currently in the Senate.

If it’s such a good idea, why haven’t we done it already?

Over the last 50 years, we have shifted to more and more Vermonters paying school taxes based on income. Currently, 2/3 of Vermont homeowners pay some or all of their school taxes based on income. Only the highest-income taxpayers – those with the most income – pay their school taxes based on property value. Property taxes came before income taxes because public education began before most people had jobs outside the home with income. Back then, property was the best and only measure of ability to pay. But that’s no longer true and it’s time our tax system reflected that. Many states make adjustments to property taxes based on income, but Vermont is 1 of only 2 states where school taxes are statewide taxes and income-based taxes are an option.

Common questions about moving to income-based school taxes

Is income more volatile than property value?

Often what people mean by volatility is that state revenue from income taxes fluctuate more with the economy than that from property. But that doesn’t matter with school taxes because school tax rates are adjusted each year to meet schools’ needs. And on a personal level, you want your school tax bill to track your income. If you lose your job, you want your school tax bill to come down. You shouldn’t be held to a higher property-based bill when you can’t afford to pay it.

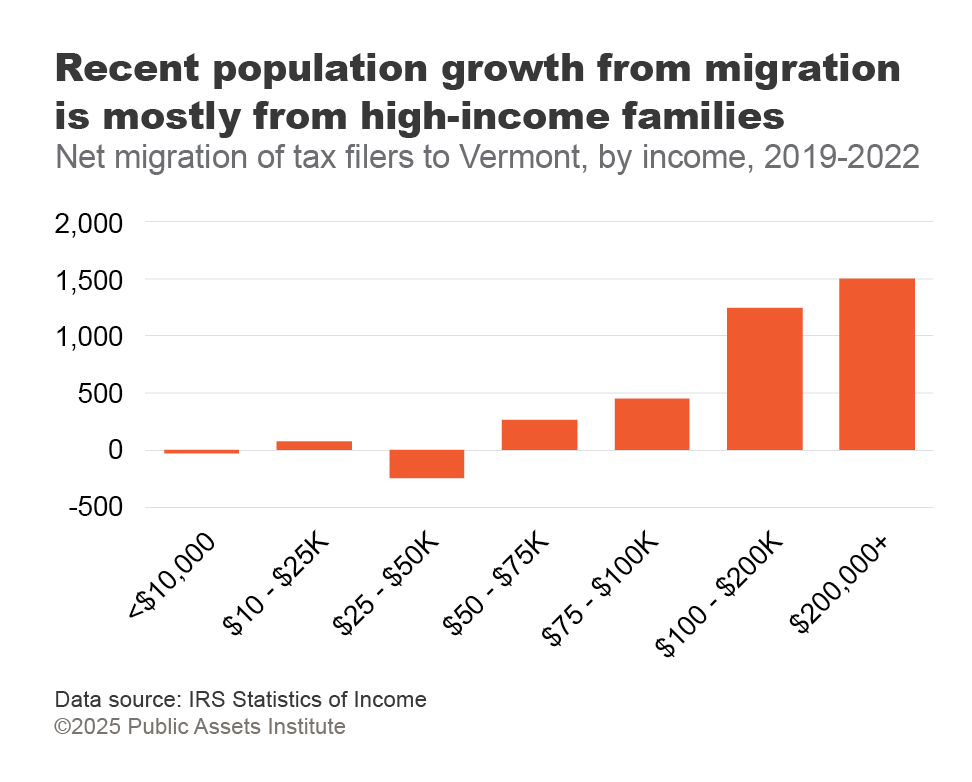

Will rich people leave the state if taxes are more progressive?

All of the research on state and local taxes does not support this argument. Very few people tend to move in any given year, and state taxes tend to be a small part of that decision. In fact, in our most recent migration report, IRS data showed that Vermont has gained high-income taxpayers since the pandemic began.

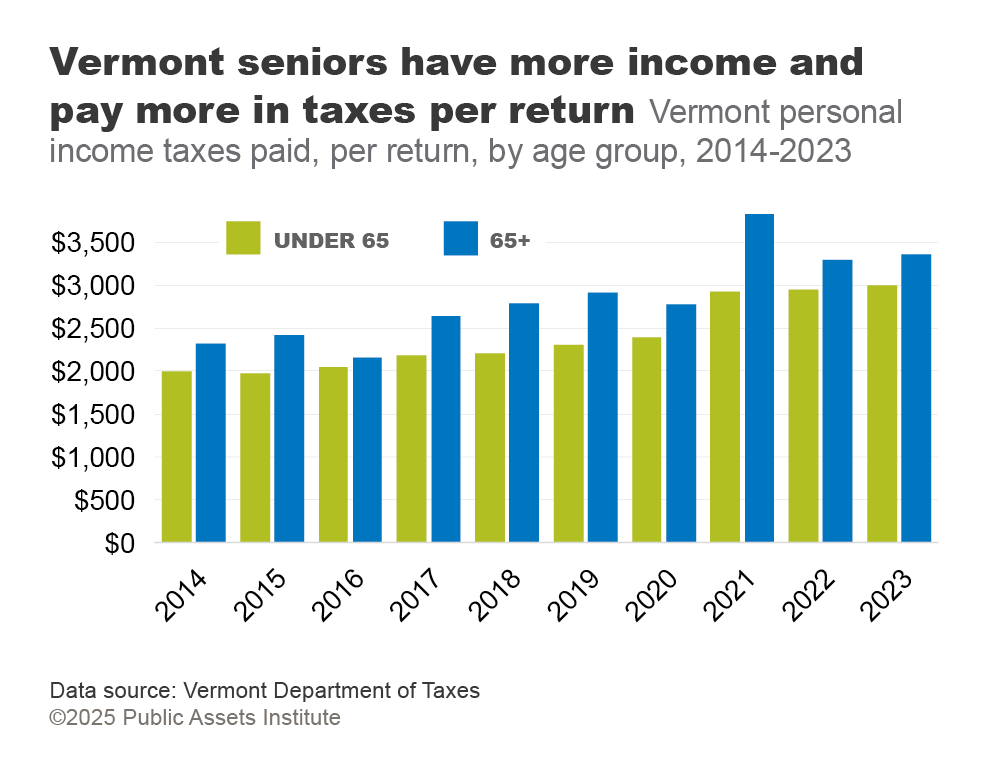

As more Vermonters age into retirement, will the income tax base shrink and the state get less revenue?

Two-thirds of Vermont’s baby boomers—people born between 1946 and 1964—were 65 or older as of 2024, meaning they were eligible for Medicare and retirement benefits from Social Security. But more Vermonters aging out of the workforce has not led to less income tax revenue for the state. Vermonters 65 and over have more taxable income on average than those under 65 and pay more taxes per return than younger filers.

Can rich Vermonters hide their income to avoid school taxes?

If rich Vermonters are hiding income, they’re avoiding the state’s personal income tax too, which is a bigger bill than school taxes. If they’re doing so illegally, it’s an enforcement problem. What’s not hidden is the incomes of those Vermonters paying school taxes based on property now: They have 60% of the income in Vermont, over $13 billion. But the current system allows them to pay based on property, which is cheaper for them and means that they’re paying a smaller share of their income in school taxes than low- and moderate-income Vermonters.